THE WORLD IN THE 1800S

Europe and the World After the French Revolution

The French Revolution (1789-1799) was a milestone in the course of world history. Inspired by radical and liberal ideas, it greatly contributed to questioning the hitherto global might of the monarchy, as well as the very existence of empires and feudalism as the dominant forms of state organisation. As a counterpoint, it made the demand for a different mode of government via the installation of liberal parliamentary democracies and the formation of nation states.

The influence and repercussions of the French revolution went far beyond the bounds of France, and indeed of Europe. On the one hand it was a source of inspiration and a revolutionary paradigm for social uprisings taking place in the immediately ensuing years all over the world, from the Balkans to Latin America and the Caribbean. At the same time, active questioning of the status quo on a global scale provoked the reaction of the empires at the time, which felt threatened by the dynamics of revolutionary violence triggered by the French Revolution, and lost no time in turning against it.

Important though the legacy of the French Revolution was for the world and for France itself, its immediate outcome was to bring France the imperial regime of Napoleon Bonaparte (1805).

Revolutions in the Caribbean and Latin America

Revolutions in the Caribbean and Latin America

The first area to take up the torch of revolution was Haiti, a French colony in the Caribbean. Up until the outbreak of the French Revolution, Haiti had been the world’s largest coffee and sugar producer, thus greatly contributing to the economy of the French Empire. This economic contribution was based on the systematic exploitation of Black slaves over several decades. On the outbreak of the French Revolution, the aristocratic white elite that represented the French Empire’s interests on the island found itself being called into question. In August 1791 a slave uprising broke out, fundamentally aimed at bringing an end to colonialism while also abolishing slavery and racial inequalities. The uprising led to the defeat of French colonial forces and Haitian independence in 1804.

In its turn, the example of the successful uprising on Haiti inspired a series of revolts against slavery in Cuba, Jamaica, Brazil and the USA. It also fuelled liberation movements in Latin America (the Latin American Independence Wars of 1808-1833), which turned against the European colonial powers of the time (Spain and Portugal) and sparked off uprisings in Mexico (1815), Venezuela (1816) and Chile (1817).

Rivalry between Empires and the Formation of Nation States

Rivalry between Empires and the Formation of Nation States

With the French Revolution, the concepts of “people” and “nation” gradually became factors in contemporary political reality. It was then that the ideologies of nationalism and liberalism began to act as rivals to the existing political and social order in the (French, British, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, Prussian and Ottoman) empires of the time. Furthermore, competition and open military conflict between these empires favoured the emergence and consolidation of nationalist movements, which turned against imperial authority in a series of uprisings and aimed, throughout the 19th century, at the formation of independent political entities in the shape of nation states. As far as Southeast Europe was concerned, successive military clashes between the Ottoman and Russian Empires (1806-1812 and 1828-1829) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1814) were closely associated both with the first Serbian uprisings (1804-1813) and the Greek Revolution of 1821, which gradually led to the formation of the autonomous Principality of Serbia and the Kingdom of Greece respectively.

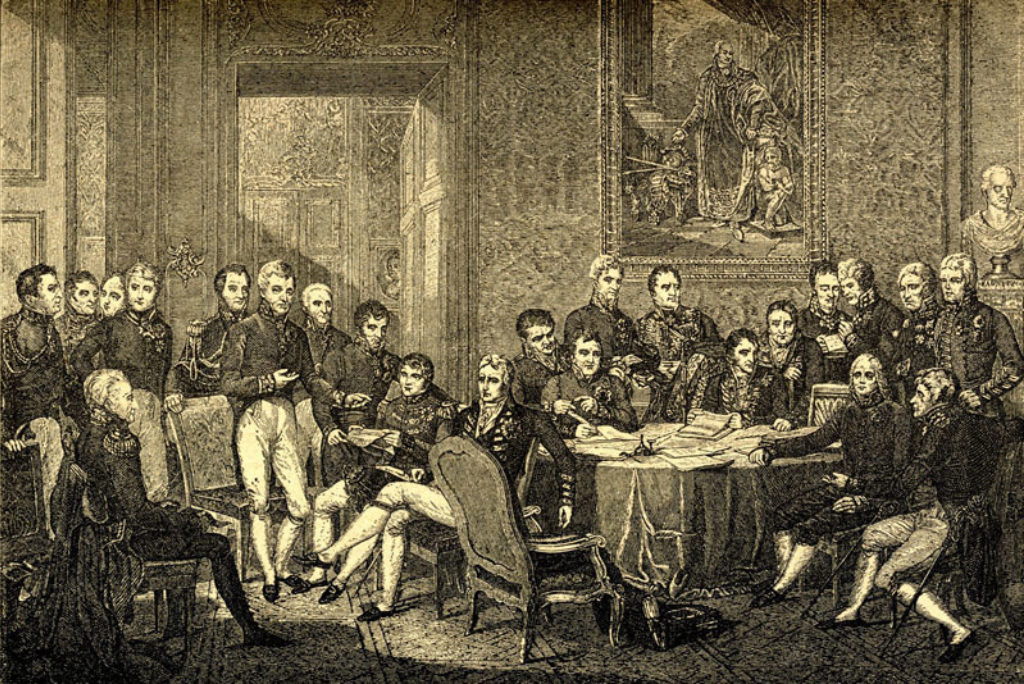

The Congress of Vienna and the Holy Alliance

The Congress of Vienna and the Holy Alliance

Even during the course of the French Revolution, both Austria-Hungary and Prussia had turned against France and attempted to restore the monarchy there, fearing that social revolution would spread to their interiors. Military conflict between France, its allies and the empires of the time culminated under the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte, extending over almost all of continental Europe. These clashes went down in history as the Napoleonic Wars, ending in 1814 with Napoleon’s surrender. At the Congress of Vienna confirming the end of the war, the victorious powers (Britain, Prussia, Austria-Hungary and Russia) attempted to redraw the borders of Europe to their benefit and restore the pre-1789 political order, reinstating deposed sovereigns all over the continent. Prioritising the Principle of Legitimacy, the empires of the time denounced the revolutions and strove to restore and consolidate the monarchy in Europe. A few months later, the empires of Austria, Prussia and Russia formed the Holy Alliance, aimed at safeguarding absolutism and quashing any revolutionary movement that might call the cohesion of their empires into question.