THROUGH TRAVELLERS’ EYES: CRETE BEFORE AND AFTER 1821

"Travels in the Island of Crete, in the Year 1817": Sieber’s Account Shortly Before the Outbreak of the Revolution

The Austrian naturalist and botanist Franz Wilhelm Sieber visited Crete in 1817, his first stop on a longer journey around the southeast Mediterranean, and published his impressions in 1823.

He was particularly interested in the poor health conditions on the island, the presence of smallpox, outbreaks of plague and the impossibility of managing the situation with the rudimentary medical facilities available.

Sieber also noted that religion was the main differentiating factor among the local population, although there were occasional cases of religious conversion by baptism and love affairs or even marriages between Christians and Muslims. Religion was a very important part of daily life, although adherence to specific religious practices – such as fasting and drinking alcohol – was lax.

Sieber’s anti-Muslim stance meant that the Christian inhabitants were willing to speak to him about their oppressive living conditions and express a revolutionary predisposition.

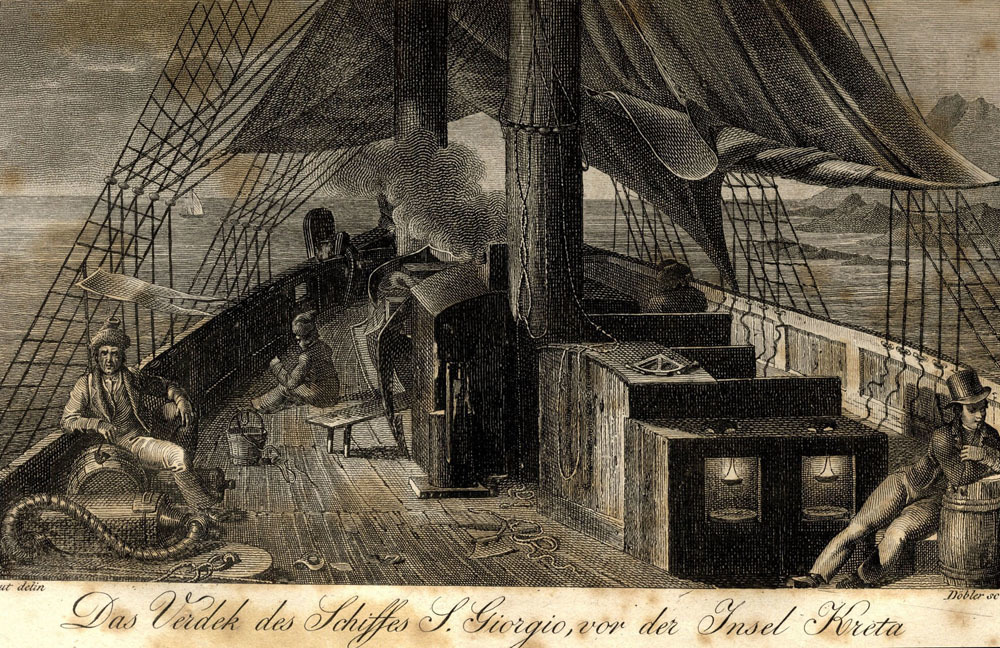

"Travels in Crete": Robert Pashley’s account following the failure of the revolution

The English economist Robert Pashley visited Crete in 1833 and 1837, later describing his experiences in his work Travels in Crete. He describes the aftermath of the revolution, with houses or even whole villages lying burnt and in ruins, looted monasteries and ravaged fields. He gives accounts of torture, rape and executions, mainly of civilians and captives. According to the testimonies he recorded, the devastation of the countryside and the violence against civilians were perpetrated by Muslim and Christian Cretans alike.

The upheaval of socioeconomic life, the widespread violence and – especially for the Christians – the consequences of the revolution and the threat of reprisals after its failure led to a significant reduction in the Cretan population. Referring to the emigration of Cretan Christians, Pashley reports: “they are now scattered through the islands of the archipelago. I myself saw several of them, at Melos, in the autumn of 1833”.