THE THIRD PERIOD (1827-1830)

The Kalisperides (‘Good Eventiders’)

The Kalisperides (‘Good Eventiders’)

Having taken Gramvousa, the revolutionaries launched a brief campaign in west Crete to stir up the Christian population anew. But the memory of the recent defeat had led to hesitancy among the Rizites (those living on the fringes of the White Mountains) and the Sphakians. Their fears were borne out when successive defeats led to the breakup of the small force that had gathered in the Kydonia area.

Various small bands were active throughout Crete over the following years. Taking refuge at times on Gramvousa and at others in the mountain massifs, they carried out lightning attacks, making rural areas unsafe for the Muslims. As they often disguised themselves as Muslims and were active during the night, they acquired the sobriquet Kalisperides (‘Good Eventiders’) or Pataxies, being more generally called Gramvousians. Military guards were stationed in various villages to tackle them, while at the same time the Muslims established equivalent bands known as the Zourides (‘Martens’), which employed similar tactics to deal serious blows to the Kalisperides.

The Merambello Campaign

The Merambello Campaign

In the belief that Crete should be an area in revolt within the context of negotiations for the formation of the Greek state, a fresh campaign was organized in the autumn of 1827, aimed at the area of Merambello in east Crete. Under the command of Ioannis Chalis the area was swiftly brought under the revolutionaries’ control, but the arrival of various new leaders with their forces led to wrangling over the issue of command and, above all, handling of the rich spoils. Having lost cohesion, the revolutionaries suffered a crushing defeat at the battle of Mochos in December 1827. Over the following days they abandoned the area by any possible means, enabling the Muslims to enter Merambello and the wider area.

Frangokastello

For the Merambello campaign, a corps of cavalry under Hatzi Michalis Talianis or Dalianis had been enlisted from mainland Greece. This small force reached Gramvousa in early 1828, by which time the entire operation had failed.

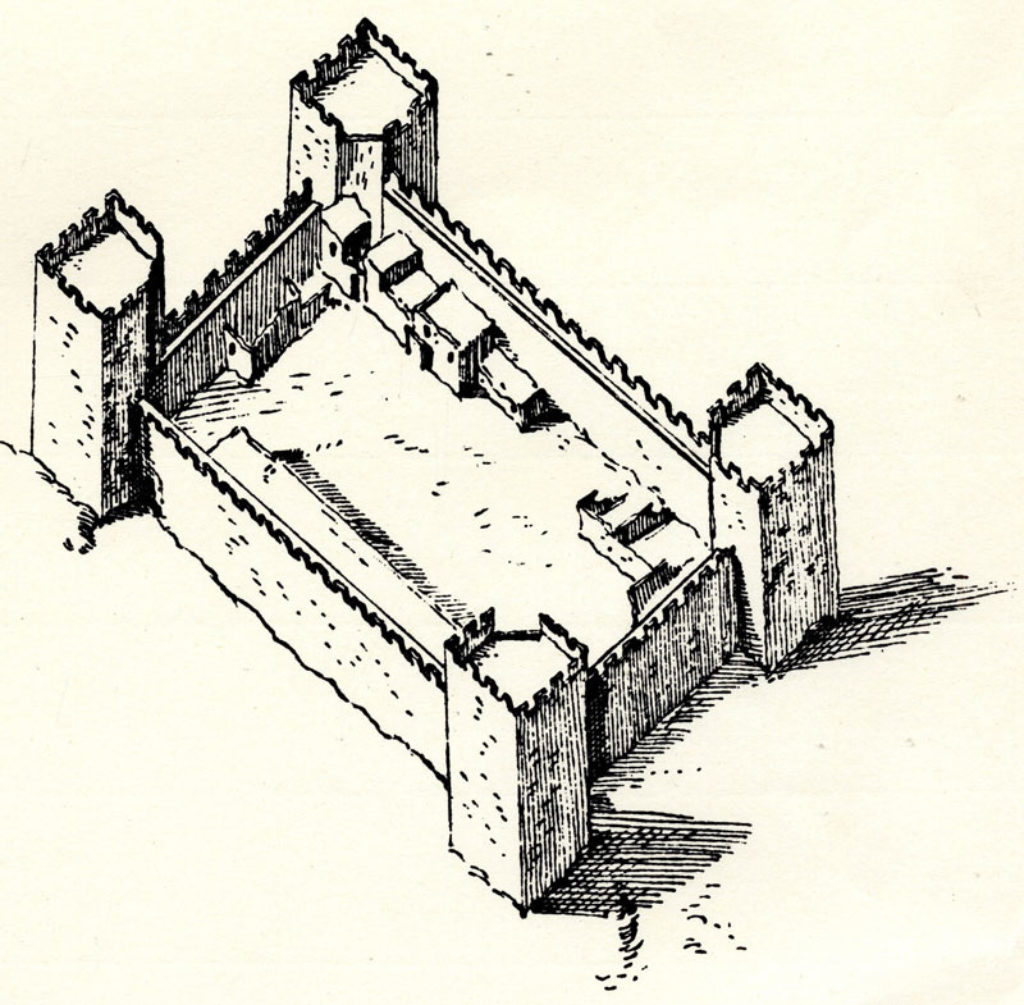

In early February the men moved to Sphakia, where it was proposed they be stationed on the small plain of Frangokastello. Cut off from its supply centres, far from the sea and surrounded by narrow passes, the Muslim army in the area could have been encircled and overwhelmingly defeated. But Talianis refused to follow the plan, provoking the remaining revolutionaries to withdraw their participation.

As many local rebel leaders had predicted, in the ensuing battle the Muslims were not slow to break down all defences, killing Talianis and blockading the revolutionaries inside the old Venetian stronghold. Muslim fears that they might be trapped in the area soon led to an agreement and the withdrawal of the besieged revolutionaries. Thereafter, however, the Sphakians and other armed bands pursued the Muslim army on its retreat, inflicting heavy casualties.

The Final Clashes

The Final Clashes

The battle at Frangokastello sparked the revival of the revolution throughout most of Crete. Yet unlike in previous years, especial care was taken to establish political and military bodies.

In search of a new field of combat, in late 1828 the revolutionaries overran Sitia, securing a number of short-lived successes. A few months later, under the command of Kapodistrias’ representative John (Johann) Hane, mass attacks were carried out on both Chania and Rethymnon, though to no substantial effect.

Exhausted by the protracted war, both sides now engaged in skirmishes, awaiting the outcome of diplomatic processes. The final decision exempting Crete from the new state in February 1830 led to some final pushes to maintain the revolution, hand in hand with repeated representations to European courts.

In late 1830 the Muslim army gradually began to retake the Cretan countryside, bringing a lasting end to the revolution that had begun almost ten years earlier.